Discussing the Recent St. Louis Tax Incentive Report With Good Jobs First’s Anthony Elmo

Good Jobs First has recently released a new report examining real estate development incentive usage in St. Louis. The report examines tax break issuance in both St. Louis City and St. Louis County. It also features an analysis of how these tax breaks are impacting school districts in both jurisdictions. Anthony Elmo, one of the study’s authors, was kind enough to chat with me about the new report, local tax incentive usage, and Good Jobs First’s recommendations to make development incentives more equitable. This discussion was edited for length and clarity.

MCM: My name is Glenn, and we’ve got Anthony Elmo from Good Jobs First. Like I said, I’ve got a number of questions for you. I enjoyed the new report! I’ve followed issues of TIF and tax abatement around town for probably about 2 decades now. And while unfortunately the conversation is kind of where it’s been for the last two decades, it is always good to have new numbers to be refreshed on what’s going on. So, thanks to everybody at Good Jobs First for putting the report together.

Anthony Elmo: Absolutely.

MCM: So, this might be weird, but I would like to start in the middle of the report for one point, and then we’ll go back to the beginning. The reason I want to start at this point is because our local elected officials, heads of development agencies, developers, etc. do a lot of work, year in, year out, to normalize the amount of tax incentive issuance in St. Louis. Whether it is the mayor… you know, mayor after mayor after mayor going out and making these deals, and being “open for business”. Recently, we’ve had Alderman Browning go on St. Louis Public Radio and essentially tell the public that it’s just not something they should even think about. This is just how it is, this is totally normal, and complaining about it doesn’t do any good. So, you know, the general public should just go along with it. So, I wanted to go to the middle of the report because It mentions how much of an extreme outlier St. Louis has become when it comes to real estate tax incentive usage. The report states our per capita rate of subsidy issuance is 7 times as high as Chicago, another metro famous for extensive TIF usage. Like I said, we have a lot of folks in town, especially elected officials and developers, who want us to think that what we do in St. Louis is normal. I would like to ask you: what would you say to our readers about St. Louis’ tax incentive usage patterns, and whether or not it’s normal or should be normalized?

Anthony Elmo: So, I would agree that it is fairly normal, but that does not mean that it is good. Our perspective, especially around students in public schools, is that they should not be collateral damage when it comes to economic development policy. St. Louis and Missouri in general have been a state and locality that are… are really devoted to these ideas and policy tools, to attract investment. And so, our contention from kind of broader research that goes beyond the report is that cities, states, and localities overstate a business’s or industry’s interest in economic incentives as the reasons that they will locate their site in a specific area. There are other business climate-related reasons that you know, Google or Meta or these other big companies are using to site data centers in Missouri and in other places across the United States. They pick them for cheap energy… they pick them for workforce that they have access to… they picked them for access to water, resources. They don’t necessarily pick them due to economic incentives, tax breaks, things like that. And so, our kind of broader contention is that companies are relying on the narrative that they need these incentives, to show up in a certain place, and they’re echoed by economic development organizations and professionals, when the reality is the opposite. These companies do not necessarily need these incentives, and the incentives are particularly harmful to communities, specifically St. Louis. Going back to the report… we’re talking about $380 million of lost revenue that we know about and can track over the course of the last 7 or 8 years, since we’ve been able to track this information. I can talk about that, too. The disclosure pieces are, I think, really important and are an important part of the story, but I think the kind of broader point I would make is that economic development professionals and site location consultants and companies, overstate the importance of tax breaks in regards to this. And that foregone lost revenue is particularly harmful to public schools, and so it’s a policy instrument and mechanism that we think should be used less. St. Louis is definitely using it to a higher degree, than other places, but there are many places that use this policy tool, and use it poorly, from our perspective.

MCM: I was gonna ask a little bit later about this, but you kind of went into the idea of the but-for clause. You know, that if it wasn’t for the incentives, the deal wouldn’t move forward. I think there’s lots of proof that’s just not true. So, we have had situations where SLDC will tout how this TIF paid off earlier than projected, but that means that the revenue was significantly higher than projected as well, right? So, was that tax break ever even necessary? The fact that a TIF pays off early is more of an indication that the TIF shouldn’t have been given than proof that it was a good idea.

Anthony Elmo: That’s right.

MCM: I also think it’s important that our readers understand that a lot of things that are approved for TIFs and large tax abatements and stuff never happen, right? And for the same thing you’re talking about: that there are a lot of other considerations that go into this. And then many of the ones that are, and the revenue numbers show that the tax breaks probably weren’t necessary to have the margin that they said they needed.

Anthony Elmo: That’s right. We’ve seen that research as well. There’s a fair amount of research that’s on our website, too, specifically in regards to Chicago, that talks about the comparisons and things like that. It has been a widely used tool in Chicago as well, but it’s structured differently. Illinois’ version of TIF actually has a potential to benefit the school district. Recently, Chicago Public Schools did use the TIF to gain public school dollars, but that’s because the entire program is structured differently than it is in St. Louis. In the report, we make some recommendations that St. Louis and Missouri in general should adopt. Shielding school property tax revenue from economic development abatements is one of them. It’s something that we think is very important for school districts to do, We recently also, and it’s just for comparison’s sake… we’ve seen other states and localities also lose serious dollars to abatements, specifically in regards to school districts. We just did a fairly large report on tax abatements in Oregon, and the negative effects on foregone lost revenue to public schools there. We believe they’re losing to the tune of $275 million a year. So, just for comparison’s sake, St. Louis area public schools have lost about $380 million in foregone revenue over the course of 7 years, while a state like Oregon’s losing $275 million a year in public school dollars to abatements and incentive programs. That’s what we know about, because they are not all disclosed to the full extent, due to accounting practices, and things like that in these states.

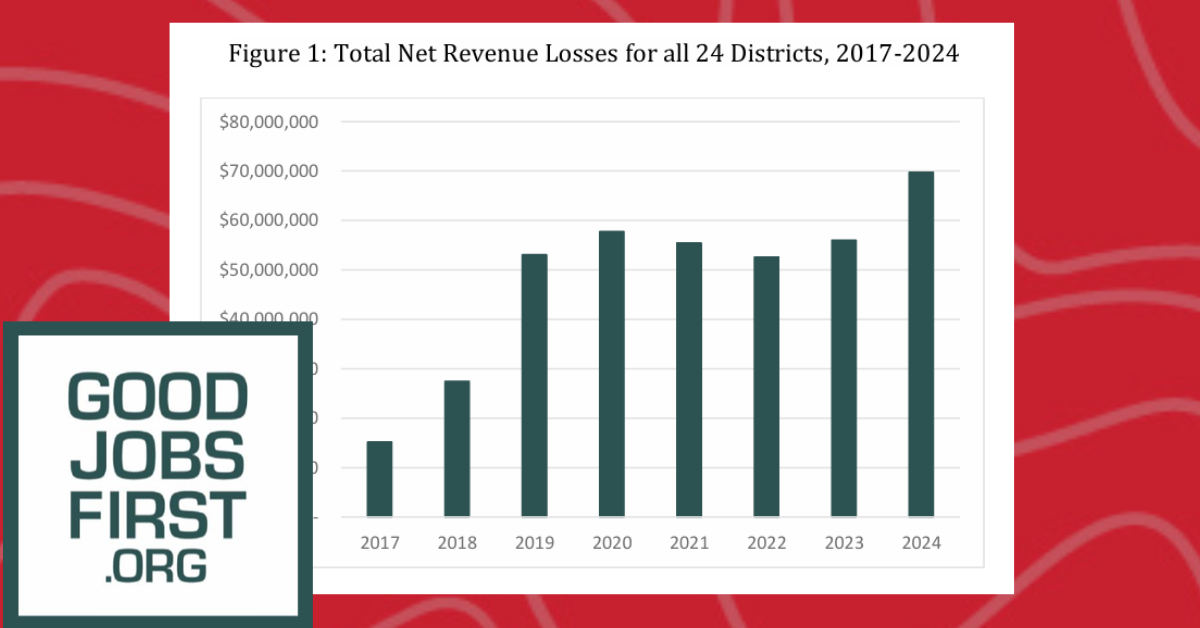

MCM: Let’s swing back to the beginning. The report starts with noting that our TIF usage has been growing at a pretty fast clip. It points out incentives in the city and the county cost local school districts $70 million in the 2024 fiscal year. It also says that this is an increase of $14 million compared to the previous year. That’s a substantial increase… almost a quarter in a single year. So what do you think is driving that increase? And, secondary question, did you find that this increase was happening faster in the city versus the suburbs, or that they were growing pretty close together?

Anthony Elmo: You know, each new deal stacks on top of the old ones. So, the losses compound over time, which is one thing to keep in mind. The more new development deals that are being approved each year, there are many that are larger in scale. We’re also starting to see the effects of the data centers. We point to that, even though the data centers are not hyperscale yet across all of Missouri and St. Louis, there are smaller projects that are affecting the issue. The fact that they’re also long-term and cumulative… we’re seeing the older ones remain in effect while new ones get added on. So, there’s no reset button. School losses only continue to grow. When you see property values are attached to this, too, as you see property values increase, the cost of the abatements goes up. That’s a factor of it as well, and that increases the money that the schools don’t get. So, those are some of the contributing factors.

MCM: That’s a good point… this process of how the numbers are stacked in the Annual Comprehensive Financial Report. Did your analysis look at when the tax breaks passed? A lot of times these projects take a while to go from being proposed to being completed. Does did your analysis add the new abatements before completion, or does that only go onto the total once it is completed?

Anthony Elmo: It’s a little bit of a difficult to keep track of that In a kind of broad and expansive way. I would say that we did look at that in a limited and conservative way, in the sense that we based the analysis on actual assessed value data that was reported by the local jurisdictions. You know, not on projected or promised investment, you know, that often comes from the companies during these deals, and the economic development agencies often tout those pieces. So, these are real booked losses. based on the GASB 77 notes that are in the annual comprehensive financial reports. Just to kind of saying a word about that, for context’s sake, the only reason that we know about these losses is because of the GASB 77 adoption in the mid-2010s. You know, the fact that we have that accounting standard, which is new, and Good Jobs first argued strenuously for, and was a leader in pushing the Government Accounting Standards Board to adopt that rule, that’s the only reason that we know about these lost revenues. We wouldn’t know about it if we didn’t have the rule applied to ACFRs across the United States. And so, it’s really a novel ability to do this analysis, when we didn’t have that tool before Because it is fairly new, the disclosure is still uneven. There are still places in Missouri that are not disclosing appropriately, and that’s why we always point to the fact that the numbers reported in the In our analyses are a baseline and a foundation. The numbers are likely higher, due to uneven disclosure practices.

MCM: That’s interesting, for a number of reasons. We just went through a fairly contentious mayoral race here. And the numbers that you guys are looking at are primarily stuff that would have happened under Tishaura Jones’s administration. There’s fairly significant usages of these tax breaks, and I just think it’s interesting because, during the last race, there was a theme that Spencer was very pro-development, and Tishaura Jones wasn’t. Just with the amount of deals announced under her time, I always thought that was, you know, somewhat disingenuous. Now, looking at the date that you guys have it does bear some of that out, There wasn’t a huge drop in the usage of these, compared to, her predecessor, Lyda Krewson, who had worked for PGAV, a planning firm that consults on these deals. I think it’s interesting that, the numbers look a lot flatter than folks might expect in between the administrations, despite what you hear during campaigns.

Anthony Elmo: Absolutely. Well, I can’t necessarily speak to the dynamic of the previous mayor and races for office. I didn’t follow that closely, but one thing I will point to as a broader trend is that there’s a major hyperscale data center project going into Kansas City that Meta is building. There are a couple more planned for Missouri. If you look at this broadly across the United States, this data center capital expenditure is the largest capital expenditure happening. We’ve seen that the United States has lost approximately 67,000 manufacturing jobs in the beginning of President Trump’s second term. And if you compare that to the data center development that’s happening, which is a giant capital expenditure but is not jobs-rich. These projects are jobs poor, or jobs light, I guess you would say. And so it’s something to keep in mind for Missouri and St. Louis. As the policymakers are building these deals, the amount of money that’s being spent per data center job is extremely high in comparison to the overall amount of jobs that are being created or sustained by economic incentives and subsidies. So, just something to keep in mind. It’s also entering the political space, too. There is some evidence that this showed up in the most recent Virginia House of Delegates races. It has popped up in other local races as well. Local fights around data centers that are popping up around the United States, and will likely pop up in Missouri.

MCM: One thing, sort of on the nerdy side of this, is that there’s been a lot of talk in the larger sort of financial world about depreciation and stuff on them, and it seems to me that, due to the fast depreciation, the chances of governments ever recouping anywhere close to what they’re sort of sold as the nominal value going in… seems it could be very difficult, right? Because, theoretically, 20 years from now, these chips should all be much cheaper, and so when the taxable value actually comes on the rolls, most of what was promised would seemingly just go up into thin air… at least potentially.

Anthony Elmo: I think that’s absolutely true, and I think there needs to be some analysis done on Missouri’s sales tax and use exemptions, and how how data centers are going to take advantage of that, specifically in regards to what you were just mentioning, which is the servers. The servers are the most capital-intensive piece of those projects, and there is a study that suggests the servers will need to be replaced every 3 to 5 years. We’re talking about every 3 to 5 years these things are going to have to be replaced, and this is in the course of a 20 to 25-year abatement or exemption. Just think about the amount of sales tax dollars that is going to compound over time for a hyperscale project. You’re talking about $5,000 to 10,000 servers, like the Meta facility being discussed in Kansas City. And so, it’s a huge capital outlay that would lead to huge foregone tax revenue loss that Kansas City schools are going to be affected by. I’m sure that we will look at that, and look at those numbers as well.

MCM: There’s quite a bit of talk about the data project at the Armory, here in Midtown St. Louis. The developer came out and said that they were not requesting incentives. Whether or not that would be true down the line, who knows? But that is what they said. To try and get an idea of financing on this, if they don’t need incentives, I filed a public information request with the redevelopment corporation that oversees the decision of whether or not to recommend incentives in that part of town. Because they have that ability, they are quasi-governmental and fall under Missouri’s, sunshine request laws. I thought it was funny, the response I got from them… they say that they never talked about financing. So this giant, expensive development that was going in, when I asked for any emails or correspondence regarding financing, private or public, I was told that there were no emails. This is a quote from the head of the redevelopment corporation: “there were no emails or correspondences regarding financing of the project or incentive requests, because no incentives have been sought for the proposed data center project.” Now, to me, it seems fairly ludicrous that a project of this size would not discuss financing with the redevelopment corporation that they would be working with. It’s a major development. So, to me, this is an amazing thing that the entity that’s supposed to shepherd it to fruition says that they’ve got nothing in writing about how it would be financed.

Anthony Elmo: I might urge you to also think about, doing a request for information on this to the Department of Economic Development in Missouri, to ask about the application of the sales and use tax exemption program, for the Armory project. It’s a separate program from the one you were just discussing, and so there could be different information available there. I also would agree with you in terms of the skepticism that they would conduct the project without taking advantage of the sales tax exemption that is available to them. That would be pretty surprising.

MCM: Yeah, I think they’re totally lying, but I was just impressed with the boldness of the lie… saying that we had no conversations about financing in writing. Public or private.

Anthony Elmo: Well, hat may be true in regards to TIF financing. You know what I mean? Like, they may be… I won’t speculate beyond saying that they… they may be referring to that, but not to the sales tax exemption, which could be much more valuable, regarding the servers and not the land.

MCM: I asked for the private financing, which would go beyond the TIF note, because I was trying to get ideas about who may be the end users. I was interested in finding a bank that seemed to be working with company X or Y.

Anthony Elmo: A lot of these projects are also governed by NDAs, too, which is something that Good Jobs First argues against as well. NDAs are prevalent in this space, and there’s little public discussion about these things.

MCM: Yeah. Alright, so I’m gonna switch gears a little bit, just because time’s running out. The report spends a lot of time noting that there’s a significant disparity in the cost to white students versus black students in the metro area when it comes to these tax incentives. Can you go into a bit more detail on the disparity? As a follow up, you also mentioned that it really impacts special school districts and students with disabilities. Could you speak a little to that point?

Anthony Elmo: Absolutely. The effects that we found were very serious, and also built upon a series of reports that we’ve done now over the last few years in regards to St. Louis. The American Federation of Teachers Local 420 originally approached us to delve into these issues. They were the ones who’ve asked us to look into them more deeply, more seriously. They were the ones who were pointing to some of the equity issues that they thought were present in school finance in St. Louis, and wanted to know whether TIF financing and the other economic incentive programs were making them worse. That was definitely something that was brought to our attention, and it bore out.

We found that the districts serving the higher shares of Black students, low-income students, and students with disabilities lose more per pupil than the wealthier, whiter districts. The same districts that are already coping with higher special education costs and unmet social and academic needs. We found that, at least from an equity perspective, that tax abatements were deepening an inequality that already existed by taking the most from the students who needed the most support. That is what we were able to find in our data. And so, I think what we want to highlight as a policy solution in regards to this, because I always want to be focused on those solutions, is that school districts need to have a voice in these these tax abatement decisions. They are the ones who are bearing the cost, but they typically have no vote on these incentive deals. They can’t veto abatements. They can’t ask for them to be reviewed, other than by entering the public square in an advocacy role. That’s their only ability to do that. How we kind of look at our role is helping give the school districts a voice in this process and bringing attention to the equity issues at hand.

MCM: You publish numbers in the report indicating that Rockwood School District is only losing $61 per student, while St. Louis City is losing $2,360 per student. I mean, that’s obviously an incredible difference.

Anthony Elmo: It really is, and it speaks to earlier where we were talking about the compounding of the deals. You know, the more deals you have, over the greater amount of time, kind of compounds up. I think you’re right that St. Louis Development Corporation, is very invested in these deals. More so than other localities. And so that’s a piece to the puzzle, too. If you have aggressive economic development officials, who are out there actively looking for deals and implementing them, then you’re going to compound your losses, compared to localities that may not be doing that.

MCM: I think, SLDC’s leadership, Otis Williams, etc, are very clear that they’re out there searching for every deal they can… year in, year out.

Anthony Elmo: Yeah, because I think from a from a metric standpoint, they’re judged in a different. They’re judged on the amount of deals that they’re signing. That’s the metric that they’re focused on. And so the size of the deal is what they see as success, less so how many jobs are purported to come in and things like that. It’s just a different kind of metric and view of success.

MCM: I think that’s an important point. Their “success” and the success of average residents in the school district may be defined differently, right?

Anthony Elmo: Yeah, that’s right.

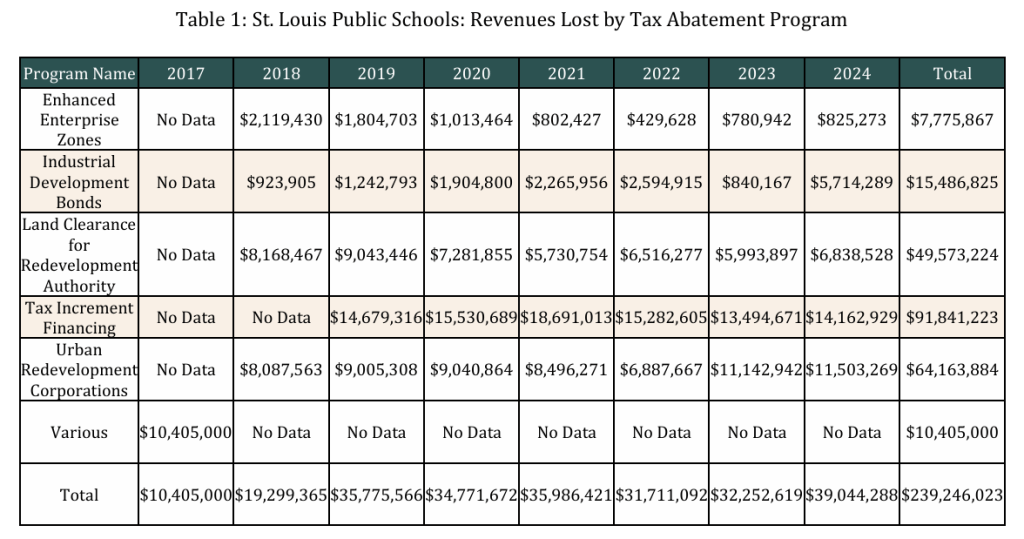

MCM: There are different motivators, and one thing that is good for one side is not necessarily good for the other, even though they’re all here in the city. And so, I know that the report says that St. Louis Public lost $39 million in 2024. Again, a big jump from the $32 million the year before. Like a 20%, or so, jump. In the report, you talk about all the difficulties that the district already faces. So, do you think that an already shrinking district can really withstand, these kinds of escalating revenue losses year after year?

Anthony Elmo: I mean, I don’t… I don’t. I think St. Louis public schools have a lot of challenges in front of them, and this is just one of them. But better to know about it and shine some light on it than have it exist in the darkness, where no one ever really knows. I think that’s at least the benefit of being able to shine some light on these things due to the GASB 77 change and others. Good Jobs First is in many ways a pro-disclosure and transparency organization, and so a lot of our work is focused on drawing attention to these types of things that fade into the background, or there’s a public narrative that more economic development and more, and better deals are better for a community. That may not necessarily be true once you start looking at the foregone revenue that should be in public schools. Because here’s the other thing… keep in mind that the numbers that we pointed to in the report are only about public schools. There are other taxing entities that are losing revenue to these abatements that we have not delved into that I would speculate is in the millions of dollars over time. I think that’s probably a conservative estimate, but we’re talking about your hospital districts, your library districts… fire, police, community colleges in some places… And so you have these other taxing entities, not to mention the cities and counties themselves, that are losing revenue to these abatements. It hollows out a community, and your tax dollars, theoretically, should be going to support services that the community needs and wants and is voting for. A lot of times, you’re letting those dollars flow out the back door and not necessarily seeing the economic development and the jobs that people are told to expect, when these incentives are promulgated. I think that’s a major problem. I think SLPS has a lot of obstacles in front of the district, in addition to the other taxing entities that are in the area, as well.

MCM: If the amount you’re losing in revenue is growing by, double digits or close to it, year after year, the amount of property tax increases is not growing at that rate, in the city, or anywhere in the state of Missouri, because it’s limited by the cost of living increase. So, you know, when you’re… whenever the rate of revenue loss of these incentives is greater than that of the cost of living assessment for a year, then that is additional revenue above and beyond any kind of inflation that is being lost. So, folks are digging the ditch deeper every year.

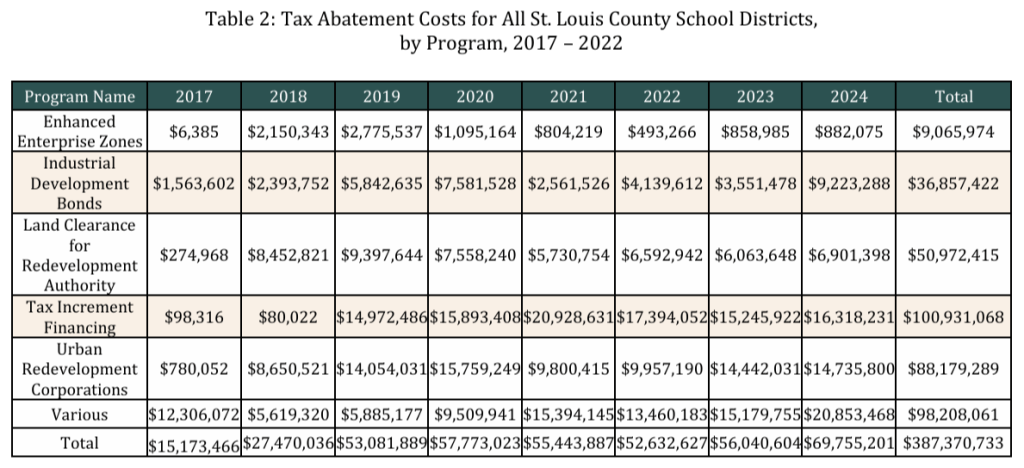

So, and this is kind of a personal quibble, TIF gets so much attention, right? It is generally the hotter topic, as opposed to just the normal tax abatement process. But, when you add up the urban redevelopment Corporations and the LCRA, and EEZ tax break, they seem to exceed the amount lost to TIF. Those are generally all known to the public as a tax abatements. There are these various processes that they can go through, but, at the end of the day, the way we experience them is kind of all the same thing… whether or not it goes through a redevelopment corporation or through EEZ, etc. Looking at the report, It appears that those numbers are higher than that lost to TIF, in recent years. Am I reading this wrong?

Anthony Elmo: No, I don’t think so. I’m driving, so I don’t have it directly in front of me to reference, but there’s a wide panoply of tax incentive programs out there that are causing issues. It isn’t just TIF. It’s other things, too. I think we point to it in the report that there’s a fairly high likelihood that there are going to be data center-related projects in Missouri that use up that create a fair amount of passively lost revenue to local taxing units. That’s in Kansas City and St. Louis. It could be in other places in Missouri as well, depending on where these things are sited. There’s a wide variety of incentive programs out there, and this is not even mentioning the federal incentive programs that many of these companies take advantage of, as well. These stack on top of each other, which is another thing that we’ve argued against, the stacking of incentive programs from the city level all the way to the federal level.

MCM: It does seem, at least in the city, the usage of TIF is not rising at the way it used to, and we’ve noticed, speaking of stacking, more of the developers, depending on the kind of development, preferring to stack a CID, a Community Improvement District, on top of a tax abatement. This is instead of going the TIF route. It seems to be easier. They don’t have to go through the TIF commission process, and there’s sensitivity to how much TIF debt is dragging down the city’s net position. To my understanding, tax abatements don’t directly reduce the city’s net position in the way a TIF note does. Do you see trends changing away from TIF usage, towards other kinds of incentives?

Anthony Elmo: It’d be hard for me to speak to what future trends look like in regards to that. Our report analysis is, to a certain extent, backwards-looking, and that’s part of the disclosure challenges around economic incentive programs and subsidies. We’re trying to look back and put together an imperfect puzzle to show us a picture of what’s happening. You know, there are very few states and cities that report these numbers and these issues in a comprehensive, easy-to-access way. It’s fairly labor-intensive to pull all these strands together, which you kind of hope is not on purpose, but it feels like it might be sometimes.. in regards to the powers that be wanting to shade things and keep things relatively secret. So, as for future trends, it’s difficult to say exactly how companies may or may not want to take advantage of these things. It also depends on where the political players involved put their emphasis… along with economic development folks, and things like that.

MCM: I want to go back to something you said about success for an agency like SLDC not necessarily meaning success for others in the community. I think St. Louis is an amazing example this paradigm never delivering, right? We’ve been doing this kind of development for decades, at this point, and those same decades have featured an almost unbroken streak of population loss. The promise that you always get from the development agencies is that all of these good things are going to come if you just wait. There’s this big payoff… it’s a quote-unquote investment… and all this stuff. In reality the public continues to vote with their feet to go.

Anthony Elmo: Well, I think that speaks to an important point: St. Louis has been has been successful in, according to some metrics, attracting development and approving projects, but they’ve been far less successful at protecting school funding at the same time, and ensuring that those deals help build up the community. A strong community will attract more varied and diverse economic industries and interests to the city. So, I think that part of the issue is that this is, in some ways, a vicious cycle. The city is attracting development, but that development is not creating an attractive, competitive place to work, live, and build up more and additional economic activity. This is evidenced by what you said: population loss and other issues in terms of making sure that that economic development activity is broad-based, fair, and equitable. It is not. I think you’re right in pointing to the fact that people are voting with their feet. Even though there is a variety of these economic development projects being pushed out there.

MCM: The city narrows in on a small demographic of people it wants to attract, and promotes successes doing that. But the reality is that, if you look at population shifts, not just in the city, but also among the suburbs, what people want are high-quality public schools. The city keeps opening charter schools and all these other things, and it’s not attracting people. And so, if you look at what folks are actually doing with their money in the larger sense, not a small slice of the demographic that you’re trying to attract to a certain kind of development in the central corridor, the reality is that it’s very obvious people want leadership that invests in their public schools. Or else, population would not be continually shifting to new districts that are performing better. And yet, that never seems to actually factor into any of these conversations with local elected officials. They act like it’s not even really part of the consideration, you know?

Anthony Elmo: The reality is it very much is part of the consideration for most companies, they are interested in placing themselves, especially when you’re talking about labor-intensive. industries or some type of a manufacturing plant… those industries are going to be attracted to places that have a high-quality school system and a developed workforce with access to colleges and higher education. There are other business climate-related issues that are important to facilities when they’re siting a location, and public schools is definitely one of them. I think this speaks to the kind of vicious cycle that is going on. As the public schools are eroded in St. Louis, it will become almost necessary, or at least there will be an impetus on economic development forces to add more and more incentives and subsidies to attract employers that would have been attracted had the schools been fully funded.

MCM: It feels like St. Louis City has had very heavy usage, and now it’s continually spreading to more and more suburbs. It kind of feels like the urban core is just sort of exporting its bad habit to more and more communities around us. Unfortunately, the leaders in those communities are also looking at things the way the city does, which is where they want to be able to say “I brought you know, development X into my district”. It’ll be a feather in their hats, so let’s get the deal done. But, at least the experience in the city is that we opened the floodgates so wide, that it is very hard to get elected officials to say no. There’s so much incentive for them to say yes, because we’ve kind of normalized this system where what success looks like is approving these giant deals that also happen to defund the schools, which are what people really want to be strong So, we’ve created this situation where, politically, the incentive is for them to do things and to support things that aren’t necessarily good for the city or the school district or rebuilding the population.

So, we’ve got 10 minutes left. I don’t want to keep you all night, and I know you’ve got other things to do. Before we go, I want to take a few minutes to discuss solution. At the end of the report, you had three main recommendations. I would appreciate if you could talk about those recommendations. I would also appreciate it if you would talk to the readers a bit about at what level of government would need to take action to make things happen. When I was reading the report, it seemed like a lot of these things were state-level, but I could be wrong. Would you mind going through the recommendations and giving our readers an idea about who should they be calling to make it happen?

Anthony Elmo: Sure. Many of these are state-level reforms. We freely admit that. On our website, there are some other reports and analyses and recommendations that we make that are based around how states can enact reforms to, for example: holding schools harmless in regards to economic development tax breaks… bifurcating school revenue from abatements and things like that. We think that’s really important. This is a state-level reform that we think Missouri should do. Especially around the data centers that are really becoming a big deal in other states, and will likely become a big deal in Missouri as well. We just firmly believe that economic development should not be financed by taking money out of classrooms, and that it creates a vicious, negative cycle for communities. Kind of building on that, if schools are going to be required to pay the price, they deserve to have a vote on tax abatement deals. Their portion of the foregone tax revenue should be up to them, the duly elected school board, or a board of trustees, to vote on whether or not deals are appropriate and a benefit to the schools and to the community that will lose that revenue in an abatement deal. That’s really important. Another part of it that we also didn’t necessarily include in the report as a recommendation, but it’s a recommendation we have echoed in other places, is that we strongly feel that there shouldn’t be backroom deals and non-transparent deals that are covered under non-payments that exclude school districts from decision-making and transparency around their foregone tax revenue. So, I think the NDAs are an issue that could at the very least be discussed at the local level. Nothing’s preventing St. Louis as a city from banning NDAs. There are other cities that have done this, in regards to economic development, so that’s one potential local policy change.

There are other municipalities in other parts of the United States that have either done it or attempted to ban NDAs as an economic development policy tool. We think that’s an important way to bring some more disclosure and sunlight to this process. So, at the very least, if school districts are going to be forced into this, everyone in the school district and locality should know about the terms of the deal. We think that’s fair and is a best practice. As the data centers come into Missouri in a more serious way, and especially in St. Louis… it’s fairly likely that there will be a hyperscale data center sited at some point in St. Louis, or in the environs around the city… that any tax breaks for, these installations should be fully disclosed, publicly reported, easy to understand, and also results in high-value jobs that are beneficial to the community for a long period of time. Again, it is a lot of state-level reform. There are the Missouri state representatives and state senators are gonna be called upon to deal with these things. But the nice thing is, is that the debate around economic incentives, subsidies, and tax breaks crosses the political aisle. You have Democrats and Republicans… conservatives, liberals, progressives, and libertarians on various sides of the political aisle that are invested in these issues. You can find unlikely and surprising coalitions on these things.

MCM: Related to that, one of our readers asked if you had examples where the cities estimated the foregone revenue and provided that information to the public, prior to the approval of the incentive. Are there any that are already doing that?

Anthony Elmo: Let me think for a second. I’m thinking about New York and Chicago as some examples, especially around their TIFs. There are states like Minnesota and Oregon where local governments have to report those things in a more transparent way. City-by-city, I don’t know off the top of my head, but I know that there are some states that have better practices around this than Missouri.

MCM: Okay, and the same reader mentioned, that there are various policy things that can be done in, via legislation, etc. but are there specific changes you would recommend the city make to SLDC’s internal processes?

Anthony Elmo: You know, one thing to look at is making it mandatory that school revenue impact assessments and estimates are done. I think that’s one thing to point to, that SLDC could… and the City of St. Louis could reform its internal processes and potentially do it through some type of a resolution or executive action that requires school-by-school foregone revenue be estimated on the front end of these deals. No deal should move forward without showing what it’s going to potentially cost students. And so I think that is probably a piece of the puzzle. And, going beyond that, requiring explicit equity parts and impact statements, when these deals are being negotiated would be good. There is a way to judge the numbers and judge the impacts, that we look at equity… specifically in regards to the cumulative burden on these districts over time. You can look at the impacts racially and by income. I think that those are relatively straightforward things that the city can do to change, because, at the very least, it would give taxpayers and citizens a window into what the effects will be on the community and on the schools. I think the other thing, too, is to think about is treating data centers differently. I think that’s probably a potential SLDC or City of St. Louis reform that could be made to treat potential data center projects as different… in regards to school revenue, compared to other incentive deals. There is a need to bifurcate them out because of the potentially large negative impacts that can accumulate over time.

MCM: I think that is most of the questions I wanted to ask you. I don’t know if you had any final thing you wanted to share with people, or, if not, I can let you go about the rest of your evening.

Anthony Elmo: I think we’ve kind of said it all at the moment, or at the very least, we’ve talked about the key things are that we strongly believe. That these effects on public schools are significant and worsening, and it’s creating a vicious cycle in the St. Louis area. The economic development that the agencies and the cities are doing is not resulting in the economic output and improvement to the community, especially in regards to schools. Schools deserve to know more about what’s going on. The parents and school board trustees deserve to get a vote on these things, and we need to be very vigilant about the potential of large-scale mega deals that could be coming down the road for data centers and things like that.