Downtown Loses Synergism to Chesterfield

News that a prominent sculpture would soon depart downtown St. Louis for Chesterfield invited many expressions of remorse. The dazzling stainless steel work Synergism, located in front of the tower at Seventh Street and Washington Avenue since 1977, will soon be the gift of the tower’s latest owners to a site in Chesterfield’s new Central Park, facing the “Downtown Chesterfield” development at the former Chesterfield Mall. Reading into this transfer a cataclysmic loss for a declining downtown would be wrong, however.

Synergism actually was born in the Chesterfield Scopia Studio, led by renowned sculptors Saunders Schultz and William Conrad Severson, so its origin already attests to the wavering relationship of downtown to the rest of the region. Schultz and Severson, master artists who helped define the Environmental Sculpture movement of the 1970s and 1980s, were already established west of I-270 by the time of this commission. That two fine artists, commissioned across the United States as well as Singapore, the Soviet Union, and Saudi Arabia, had posted up in the western suburbs in the 1970s demonstrates how the city of St. Louis lost many battles decades ago. In a way, the relationship of Schultz and Severson to the corner of Eighth and Washington illustrates that the city was already a suburb of its suburbs fifty years ago.

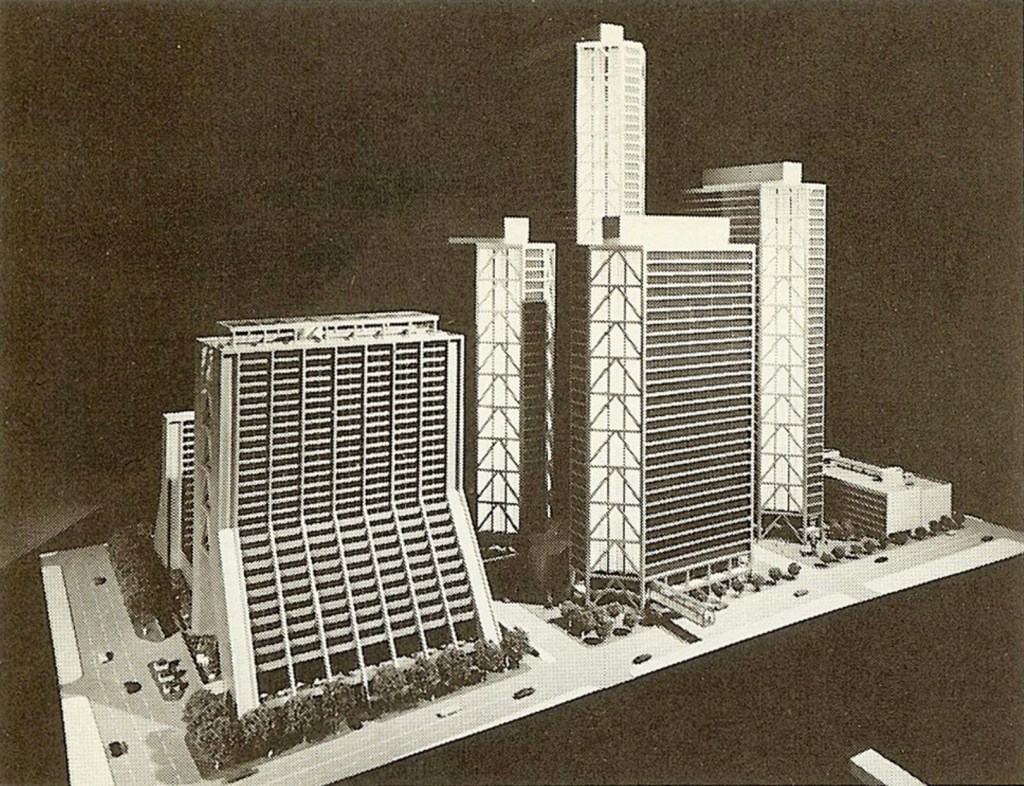

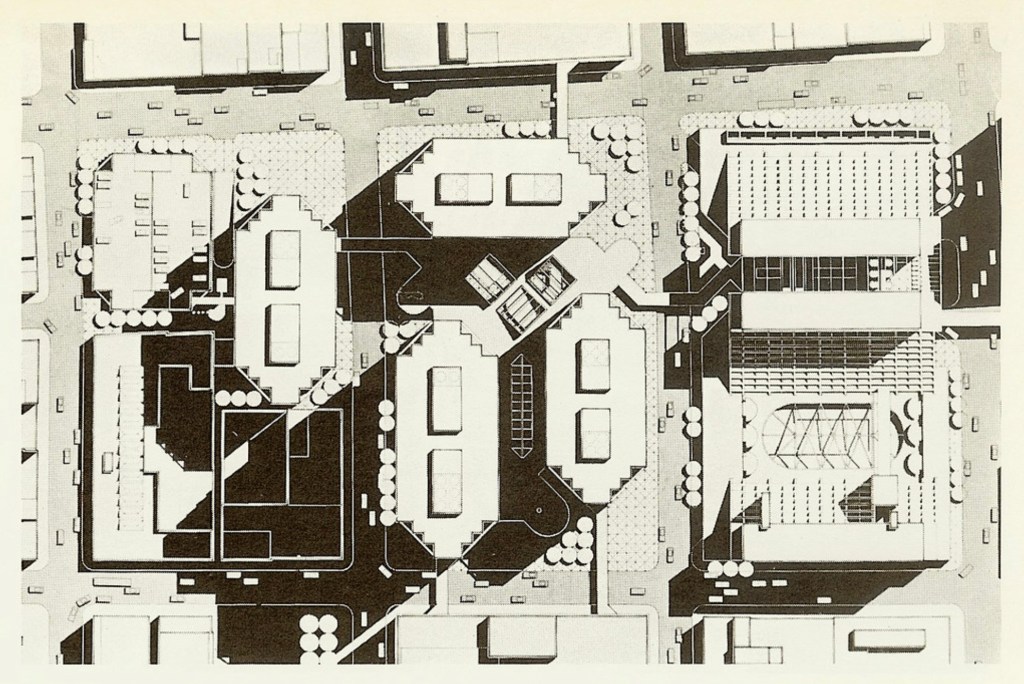

The sculpture was a defining work of public art for the Mercantile Tower when it opened in 1977. Mercantile Tower was the only fruit of a larger scheme called “Mercantile Center” led by Mercantile Bank, the long-since-merged St. Louis financial powerhouse. The bank announced its plans for Mercantile Center in 1972. Mercantile Bank originally envisioned a set of towers and a low-rise office/mall building, a project that different developers would complete in 1985 as St. Louis Centre, flanking both sides of Seventh Street. The project promised 3.3 million square feet of Class A office space, 1.8 million square feet of retail space, and 1,000 hotel rooms.

Mercantile wanted to hail the revival of the old city core in the city’s most perilous decade. The plan was flashy: four matching hexagonal-shaped high-rises with iconic K-braces on the corners. The K-braces would open each corner for a saw-toothed plan providing 16 corner offices per floor. Mercantile Center was poised to draw corporate St. Louis back to downtown from Clayton and the emerging bastions of office parks up and down I-64/US 40 and I-270. Chesterfield barely registered as a concern for downtown in these years, but by the mid-1980s would prove to be a powerful counterweight to downtown.

Atlanta-based architectural firm Thompson, Ventulett & Stainback designed the prototype towers for Mercantile Bank. The bank – one of the city’s most powerful – failed to raise the capital to develop more than a single building where it would place its headquarters. The 483-foot tower would become Missouri’s tallest building upon completion, and its shimmering glass and shiny metal spoke to a vision of the city core where rejuvenation of corporate presence would stomp out prevalent decay.

Schultz and Severson rode the waves of both urban renewal and suburban outmigration, with their own choice of studio location a quiet declaration of sorts. The duo developed the bas-relief brickwork on the 250’ east face of the Council Plaza tower, completed in 1967 as part of that Teamster-led project. Entitled Finite-Infinite, the work was restored in a 2010s renovation. The sculptors also crafted the symbolic stone sculpture at the Optimist Club Building on Lindell Boulevard, built in 1961. Both projects were designed by the architects at Schwarz & Van Hoefen, with major contributions from the late architect Richard Henmi. In this era, the sculptors also worked on pieces in St. Louis County, including the interior art at B’Nai El synagogue in Frontenac (now demolished), which wrapped up the same year that Synergism was installed.

The sculptors worked all over the country with both urban and suburban art projects at corporate headquarters. Schultz and Severson summed up their vision for working with business sites – suburban sprawl and urban renewal alike — as “reperceiving the corporate reality, defining through the art medium the ideal function or goal of a company.” Certainly, their work became distinguished, but their habit of switching between the efforts to revive forlorn downtowns and those drawing corporations out to modern suburbs shows the long ambivalence to the fate of older cities.

When the Mercantile Bank headquarters opened in 1977, St. Louis was experiencing some of its most rapid decline. The Pruitt-Igoe housing development was being demolished after less than 20 years in operation. The city had just concluded a fiery episode in which city leaders had elected to endorse the deliberate disinvestment in certain parts of the city, redirecting those resources in an effort to save other, whiter neighborhoods. Another sculpture downtown, Richard Serra’s Twain at Eleventh and Market streets, just replaced an already-abandoned 1967 urban renewal park block on the Gateway Mall. Serra’s disjointed rusting steel plates evoked the city’s evident fragmentation as well as the hold of its past.

Synergism will soon be departing downtown to return to where it was created, with L. Wayne Swisher as the chief fabricator for the artists. It will make a stop at the BLA Studio led by Dave Blum, Leef Armontrout, and Joe Bacus, where accumulated deterioration will be repaired. Yet its trajectory seems only to underscore the regional malaise in which downtown has long lost its grip on being the region’s financial and symbolic center. From Chesterfield, back to Chesterfield – with the key difference between 1977 and 2026 being how much more developed and wealthy Chesterfield has become. Downtown remains the space that a metropolitan region still occasionally exalts as its center but perpetually disavows as a place for major civic responsibility.