Book Review: Canfield Drive: A History of Race and the American City on a Street in St. Louis

Knox Averett, Matthew. Canfield Drive: A History of Race and the American City on a Street in St. Louis. First Edition. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2025.

Matthew Averett, a native St Louisan, is a Professor of Art History at Creighton University, where he teaches architectural history. In his introduction to Canfield Drive: A History of Race and the American City on a Street in St. Louis, he positions the book as “the first comprehensive urban history of the Black spaces of St. Louis, from the founding of the city to the Ferguson Uprising.” For Averett, St. Louis includes the whole of the city and county bearing the name. This is true enough, though many of us who spent time in the streets during 2014-15 thought some geographical specificity was needed for a full understanding of issues at play. This is especially true, when we add the killings of Kajieme Powell, on the city’s north side, and Vonderrit Myers Jr, on the near south side, by St Louis Metropolitan Police Department officers.

Part of his critique of status quo media reporting/isolating the “Ferguson Uprising’ is to see it as a given that Ferguson and Canfield are exceptional, in an attempt to “quarantine the violent racism that killed [Mike] Brown to that one place.” The author positions this history of Black spaces in St. Louis as exemplary of national issues of racism and its urban planning tools, practices, and outcomes, rather than isolated exceptions occurring here in St. Louis.

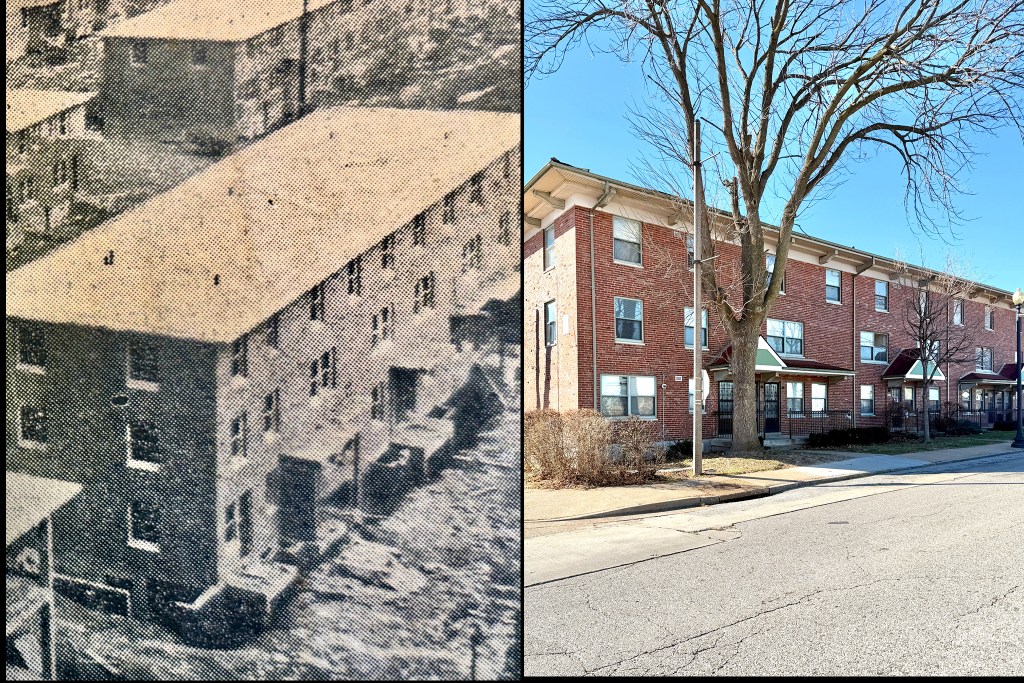

The body of the text provides a look through time, which provided me with a great deal of information with which I was unfamiliar. The book weaves a narrative encompassing Targee St, the changes in West Belle Pl, the Ville, and Fairground Park. It then continues connecting threads that run through Carr Square Village into Mill Creek Valley, Pruitt-Igoe, eventually leading to North County, Northwinds Estates, and Michael Brown Jr’s death on Canfield.

The historical overview is well worth reading, and it provides the needed local context about the segregation practices that corralled Black St. Louisans into areas of concentrated poverty, generation after generation, with Canfield as a continuation of this pattern. It is not a book about activism in the face of gross discrimination, but a history of what people with power have done, over and over again.

One useful turn of phrase is the description of changing levels of economic class in an area is to call it a “hand-me-down” neighborhood or home, as maintenance decreases and disinvestment increases over time until Black folks are allowed into areas that were previously off limits. Eventually, between redlining and a lack of economic opportunity, once-thriving buildings and blocks become abandoned.

Averett, through the lens of St. Louis, concludes with this:

“As this book and other US urban histories show, Americans have gone to great lengths to keep racial segregation alive, even at the cost of destroying our cities. Slums were cleared out only to build Pruitt-Igoe in their place; the name of Canfield Green was changed to Pleasant View Gardens, but these moves only continue to mask the fact that most Americans have no desire to face, let alone remediate, the root cause of so many of our urban failures: racism.”

Lastly, I understand the perspective and even the value of showing how Ferguson is not a singular and unique place. Rather, it is part of a larger system that is at work from coast to coast. But, for sure, we should all remember those who rose up in outrage, anger, fear, and love for their people and community. They activated what would become known, across the world, as the Ferguson Uprising.