City Throws Away Millions of Dollars Previously Invested in Interco Plaza

On Friday, October 24th, the St. Louis Board of Aldermen voted 10-3 to sell the green space named Interco Plaza for $275,000 to StarWood Group, owner of the former St. Louis Post-Dispatch Building to the north. StarWood Group plans to convert the public space to a parking lot, claiming that more spaces are needed to attract more tenants. In one of the most overparked downtowns in the nation, the claim seems facetious as a literal statement. Most likely, the developer simply wants control over a park whose lapse back into public space would entail that, well, any member of the public may use it.

Interco Plaza has not been publicly accessible for four years, as the City barricaded the space after evicting a homeless encampment there. The plaza has sat surrounded by a dour chain link fence, with the St. Patrick Center on the south side. There is the visual contradiction of an attempted homeless strategy: restriction of unsanctioned dwelling and promotion of nonprofit providers. Whether or not this strategy best serves the interests of homeless people, it has induced several sites around downtown where temporary or semi-permanent fencing and barricades have stood. City Hall’s own lawn was fenced off by Mayor Lyda Krewson and remained fenced until Mayor Cara Spencer removed the fencing.

Spencer has indicated that she will approve the ordinance conveying Interco Plaza to StarWood Group. Opponents of this transfer have raised the question of whether a 2007 referendum-passed law requiring a public vote before the City can sell park space means that the ordinance will be illegal. That law came out of the city’s sale of a part of Forest Park to healthcare behemoth Barnes-Jewish Children (BJC) under the administration of Mayor Francis Slay. City Counselor Michael Garvin is threading the legal needle, opining that Interco Plaza was never declared a city park, so therefore does not fall under the charter provision requiring a public vote. Alderman Michael Browning (9th), one of the three nay votes, argued that the City of St. Louis lists Interco Plaza as a city park on its official city park website.

The basis of the sales price comes from an appraisal report—dated September 23, 2025 –by Lauer, Jersa and Associates (LJA), notably addressed to StarWood principal John Berglund and not to any city agency. LJA did not prepare a detailed sales comparison for the appraisal, stating in its report: “The Sales Comparison Approach is not a specific scope requirement of this assignment. Characteristics specific to the subject property do not warrant that this valuation technique be developed. Based on this reasoning, the Improved Sales Comparison Approach is not presented within this appraisal.” The appraiser does use four other land sales to determine land value, with only one downtown comparable and three others located in West End, Bevo, and Dutchtown. These properties are all commercial.

Whatever happens to the outcome of a challenge to the legality of the sale of Interco Plaza, and whether the use of a single appraisal seemingly commissioned to be favorable to the buyer and not the seller, the sales price still represents a tremendous undercutting of the City’s own investment in building and maintaining it. Selling a piece of public property in a supposedly desirable downtown location for less than what a flip goes for in Dutchtown may raise eyebrows in and of itself, but a look at the history of Interco Plaza allows the financial loss to be quantified.

The plaza originally was planned to shield the open cut of the Illinois Terminal Railroad’s electric interurban and freight lines, built in the early 1930s to serve a major scheme for a Midwestern freight hub as well as an interurban passenger station. The Great Depression scuttled the original plan of a tall skyscraper at the northeast corner of Washington and Tucker (then Twelfth) as a signature passenger terminal and sleek office building. Instead, the Central Terminal Building (1932) to the north (purchased and renamed for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat newspaper in 1959) became the only realized part of the project. There, the passenger lines connecting St. Louisans to Decatur, Springfield, and Granite City ended. The last interurban car ran in 1956, but the rail cut continued as a freight line delivering paper to the Post-Dispatch and Globe-Democrat into the 1990s. (A third newspaper, the St. Louis Star-Times, built the St. Patrick Center building in 1936 and also made use of the freight line.)

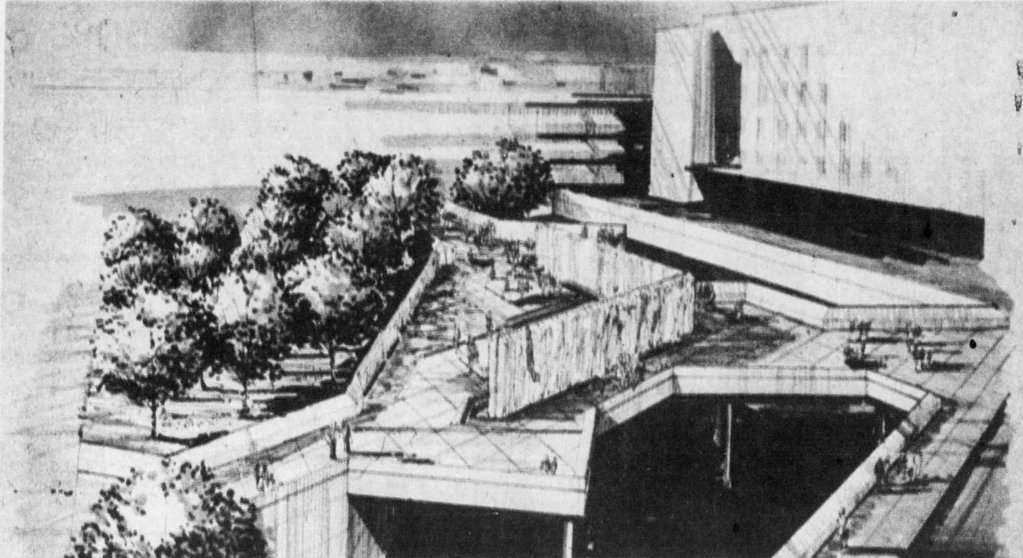

In 1969, the Convention Plaza Redevelopment Corporation first proposed rebuilding the area to the east of the newspaper buildings as an office area. Anticipating the construction of the original part of the current America’s Center (which opened in 1977 as the Cervantes Convention Center), developers pushed for new construction as well as the concealing of the railroad cut. In 1977, the engineering firm Sverdrup & Parcel—located in today’s St. Patrick’s center–proposed relocating to a new high-rise to the northeast. The project proposed the Interco Plaza as a hardscape public space concealing the still-active freight rail below. The plaza would not be a full lid, and would feature paths and benches with open ventilation shafts. Fountains concealed the walls around the cuts.

Interco Plaza’s construction was supposed to cost the city’s Land Clearance for Redevelopment Authority $468,000 in 1977, which was paid for by a federal grant. The name of the plaza came from the International Shoe Company’s holding company, which was the successor to the Illinois Terminal Railroad in owning air rights over the cut. In the end, the park cost $1.09 million to build, according to plans from the architectural firm of PGAV. Adjusted for inflation, the original cost of building Interco Plaza today would be $4,876,473.83. Work began in November 1979 and was completed in May 1981. In an article showing workers lounging in the new space, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch called Interco Plaza a “landscaped park” in its May 24, 1981 issue.

By 2002, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch dubbed Interco Plaza as “neglected” and reported in the December 18, 2002 edition that a fountain at the park was being removed and filled to become a garden. Then-Alderwoman Phyllis Young (7th) stated that the fountain had been inoperable for years. The newspaper referred to the space as a “city park” in the article. The removal and rebuilding of the fountain was to cost the City $37,618. In 2025, this is $67,917.32 when adjusted for inflation.

In 2009, the City began removing the old rail cut (called a “tunnel” in many accounts, although most of it was never enclosed) in order to infill the space and rebuild Tucker Boulevard. The overall project, awarded to Gershenson Construction Company of Eureka, cost $35 million. The Obama stimulus act provided $16.5 million of that in a federal contribution. As part of the project, Interco Plaza was rebuilt as a very modest park atop new infill. Paved areas and lawns provided a fairly uninspired space. This writer could not locate the specific cost of rebuilding Interco Plaza, which was folded into the overall project contract.

At the very least, the City of St. Louis can be proven to be $4.8 million in the hole for building Interco Plaza, but that number is far too low given the 2010 infill and rebuilding. Selling for $275,000 fails to come close to breaking even. Just looking purely at the City’s investment, the sale of Interco Plaza is beyond “giving it away.” Again, whether the sale is legal or the park is useful as open space are not the main questions of this article. Here we are looking simply at sunk costs and return on investment. With the impending sale of Interco Plaza, the City is giving away millions of dollars of previous public investment.

UPDATE: This article was updated to correctly identify the company that sold air rights to the city, allowing the park’s construction.