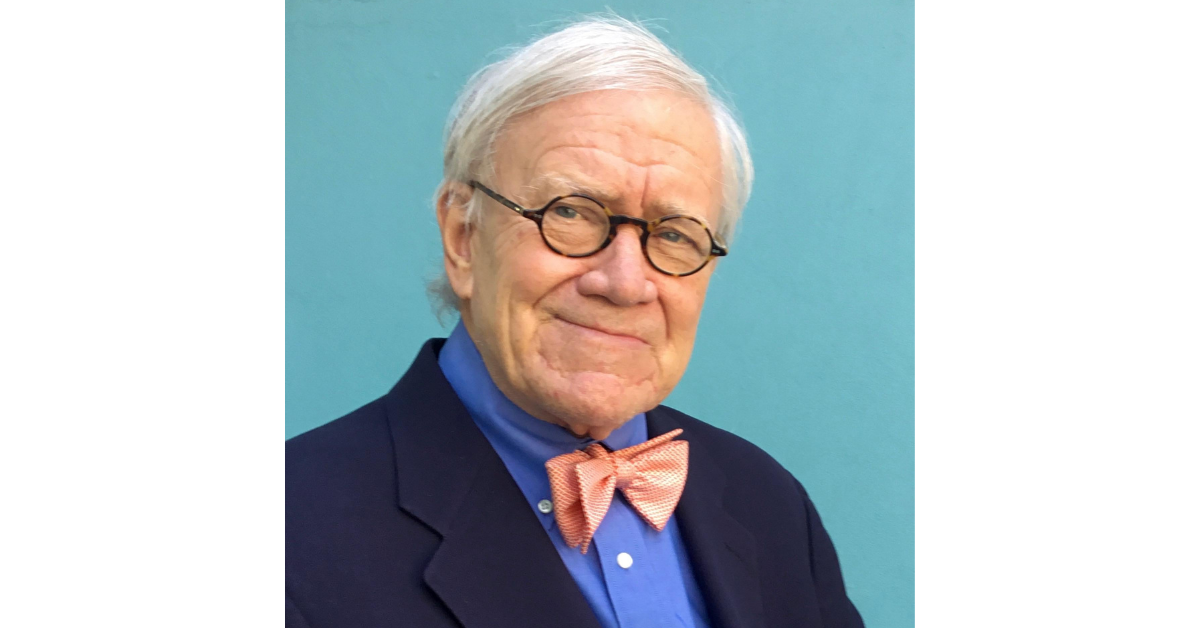

Michael Allen: Remembering Bob Duffy

By Michael R. Allen

Earlier this month, St. Louis lost one of its most reverent suitors, ardent champions and earnest cultural fixers. When I read the news that Robert W. Duffy – known to most of us as Bob Duffy, Bobby Duffy or even Uncle Bobby – had died, my spirit fell into a salubrious mood. Not only has the world lost a real champion of the public intellectual life of St. Louis, but it may also have lost the very kind of journalist that he was. Bob Duffy critiqued and cajoled, charmed and commented, not simply to earn a check or build social capital but to actually mold the consciousness of an American city. His work allowed St. Louis to sustain cultural deliberations as rich, deep and sometimes comic as any in New York, Chicago and Los Angeles.

I am old enough to know an era where Bob was not alone. Those older than me will know names such as George McCue, E.F. Porter, Jr., Charlene Prost, Philip Kennicott, Greg Freeman, Bob and Agnes Wilcox, Diane Carson, Robert Hunt, Elizabeth Vega, Sylvester Brown, Jr. and many more – journalists whose cultural imagination spanned architecture, music, visual art, opera, theater and performance, and who delivered to St. Louis spirited critical essays with conviction and point of view. Today, some may not even realize the breadth of critical cultural writers platformed across mainstream media sources, whose writerly fodder was neither the latest political Twitter feud nor nonprofit gossip. The city cooked with cultural criticism, which challenged producers of culture to think twice but more importantly, built audiences who actually came out to see the latest play, building, exhibition or event.

Bob Duffy nestled into the local critical tradition with an art history education from Washington University in St. Louis, a single-mother Arkansas childhood and a real interest in journalism. Bob was not the elitist fitting into a newspaper when he started writing arts and architecture criticism for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. He was already a seasoned reporter who had started where all reporters start – on the most basic and most banal items. Bob Duffy practiced how to talk to ordinary people through newspaper writing, and rarely dipped into more academic or exclusive formats – despite a demeanor where his panache and erudition would have allowed him to blend in. Bob wrote to the masses, despite his acceptance in elite circles.

Bob Duffy has the opportunity to focus on architecture as a major concern of his writing, which again seems impossible for any writer working in a second-tier American city today. (Full-time architecture critics only exist in newspapers in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Philadelphia and Dallas now.) Through Bob, St. Louisans understood the tremendous folly of demolishing the Arena for an office park, even as Bob Cassilly proposed a creative aquarium project. They read about the countless stupid urban design follies of the 1980s and 1990s downtown, from the agonies of the Gateway Mall to the placement of the Thomas F. Eagleton Courthouse blocking views of the Gateway Arch. Perhaps most pointed and against the grain of not only the political establishment but also his own newspaper — which had fallen under the sway of Mayor Francis Slay’s PR machine – was Bob’s eloquent warnings that trading the Century Building for a parking garage was not simply a question of historic preservation but of cultural values.

Today, as the garage that replaced the Century Building has never been more than half-full, the Old Post Office it supposedly resuscitated is now closed to the public and has lost all of its hotshot early-wave tenants like a library branch and restaurants, the city can only somberly note that it should have listened to its esteemed critic a little more closely. Bob correctly spelled out that the developer-driven, short-sighted demolition of the Century Building was an attack on the civic energy and ambitions of downtown residents and small business owners. What a harsh premonition. I know that Bob Duffy was not proud to have made the correct call. Downtown today is bereft of street-level vitality, let alone a critical mass of civic-minded small businesses. Downtown’s residents have gone from a civic vanguard to a bedroom community terrified of insane driving and gunshots in the twenty years since Mayor Slay and the civic elites forced the Old Post Office plan through the channels.

Yet Bob was not simply an oracle of the grand misfortunes and opportunities of public architecture. He helped convene a charette for a section of Olive Street in the Central West End back in 1999. At the time, that area fell into a gap between the gentrified part of the neighborhood and Fountain Park to the north. Its possibility as a connective space inspired Bob. When I first interacted with Bob, it was after he wrote a column about a garage in Lafayette Square near the old City Hospital. I responded with a short letter that he reprinted in his column. That was 1997, and I was 16 years old. Reading my own words in the daily newspaper propelled my confidence in ways I am still realizing.

As I came to actually know Bob, through my four-year tenure on the staff of Landmarks Association of St. Louis where he was a Board member and later Counselor, I realized that the man spent an inordinate amount of time doing social work every bit as tremendous as his critical journalism. Bob mentored, connected, encouraged, supported and challenged all of the people around him he thought could make a difference in St. Louis. He could be quite specific, too. Once, I posted on Facebook that I was looking for a seersucker suit. Bob soon sent me a message that I was due to arrive at a salon the next day, with an address and time. I knew it was his own home address, but I did not expect to arrive to a smiling Bobby Duffy handing me one of his seersucker suits – needing tailoring, but within the range of my sizes. There was even a personally selected madras bowtie to match. I still wear and cherish that suit, which reflects Bobby’s old-school sense of style as well as his compassion – literally giving me the suit on his back.

Bob Duffy envisioned his role as a cultural critic as something like a theatrical impresario. He assembled the large cast needed to give a fallen city a world-class cultural sphere, spanning all the visual, literary, theatrical and musical arts. His care for both writerly craft and the social ecology of the city may never be surpassed. In his company, in his words, in his circle – anyone could feel like St. Louis was every bit as vibrant as New York or Paris or Buenos Aires or Cairo. May St. Louis and every peripheral city continue to find such forces.

Michael R. Allen is visiting assistant professor of history at West Virginia University, and until last year, executive director of the National Building Arts Center and a faculty member at Washington University in St. Louis.