Still Putting Out the Fires of 2008

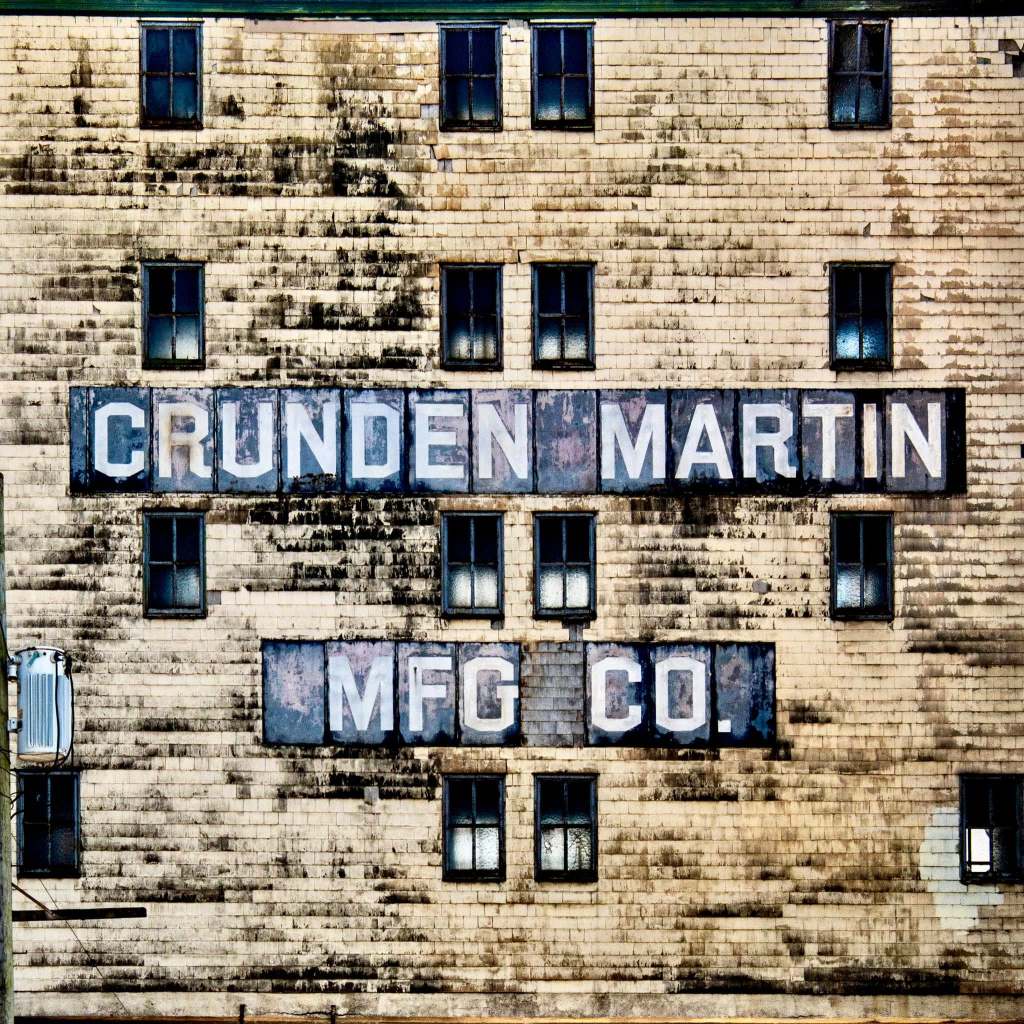

Early on the Saturday morning after Thanksgiving Day, St. Louisans were hit with a wave of spectacular images and videos of the Crunden-Martin Manufacturing Company warehouses engulfed in a six-alarm fire that devastated the historic complex. Views of mighty red-brick walls framing flames reaching far above the six-story buildings shocked many. Clearly, most of the Crunden-Martin complex will never reap the benefits promised by a recent adaptive reuse project. At least one person, a homeless resident, is still missing; thankfully, the Fire Department worked diligently to rescue many others.

People have immediately pounced on Good Development Group, the development company that has spent the last three years on an ambitious $1.2 billion proposal to redevelop Crunden-Martin and many buildings and sites in a 100-acre area surrounding it. According to Good Development Group, Crunden-Martin was the centerpiece of a development that envisioned a construction and materials technology center, retail, new housing, and even an exhibition space for the National Building Arts Center.

After closing on $200 million phase one financing in 2024, Good Development Group and its partner Robert Millstone seemed ready to set sail. Yet Crunden-Martin’s hulking five-part mass stood empty and apparently not fully secured. Some online commentators have insinuated bad faith from Good Development Group, noting that more than one historic building promised for rehabilitation by a developer lately has met its end in ash and the wrecking ball. Yet Good Development Group and its architect, Eldorado, have developed a lot more than dazzling renderings for the project. Their efforts to get the rehabilitation of Crunden-Martin to fruition have seemed to be serious, from adding Millstone as a local equity investor (real risk) to allowing grassroots art festival Artica to use their land in the area.

The western block of Crunden-Martin – a complex built in stages between 1904 and 1920 – had already suffered a severe fire in 2011. Ironically, that section seemed to have fared the best. Its already-burned timbers disintegrated, but its sturdy brick walls seem unscathed. The developer had already envisioned a creative, open-volume space here, so perhaps that will remain viable.

Some have lamented the loss of the former factory complex, since it is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Crunden-Martin received National Register status in 2005, after a previous developer seeking historic rehabilitation tax credits – for which National Register status is necessary – commissioned the designation. That listing provides a key to understanding why the fire this past weekend may be seen as the return of an economic curse.

As with many historic buildings in the city, Crunden-Martin was one of a wave of National Register listings fueled by “predevelopment” discovery in the pre-2008 boom. Developers flew National Register listings like kites to ascertain whether historic tax credits could be a viable source in the financing stack. Many of the city’s recent losses of historic industrial buildings around the riverfront can be linked to this era’s excess speculation and the subsequent retraction.

The Norvell-Shapleigh Warehouse (1904-6) at 2nd and O’Fallon on the north riverfront burned in February 2024. That fire demonstrated that a stately historic building occupying a full city block can be completely destroyed by what starts as a small fire. Nearby, at 1st and O’Fallon streets, the Beck & Corbitt Warehouse (1911) went up in a blaze in October 2022 – another total loss. Both buildings were contributing resources to the North Riverfront Industrial Historic District (National Register listed, 2003), a project funded by Trailnet. At the time, Trailnet was seeking to create a frame for redeveloping the nearby Laclede Power House (1904) into a trailhead bike rental facility, café, and visitor center for the North Riverfront Trail. Speculators followed Trailnet by snapping up industrial buildings. Unfortunately, the dreams of that era fell victim to the 2008 financial crisis.

West of I-70, the McGuire Moving and Storage Building (originally the Sligo Iron Store Company Building, 1903-11) on 7th Street went up in a blaze in January 2024. That warehouse had been listed in the National Register in 2010. Its designation was part of a last-ditch effort to reinvigorate the Bottle District redevelopment first pitched in 2004 by McGuire Moving and Storage and later sold to a partnership that included Bob Clark of Clayco and Paul J. McKee, Jr. of Northside Regeneration.

McKee’s Northside Regeneration may be the ultimate example of fires claiming one major majestic historic building after another, as neighbors watched fires claim building after building. From the James Clemens Jr. House to the Brecht Butcher Supply Company Buildings to numerous elegant 19th century homes, buildings in Northside Regeneration’s footprint have burned with unfortunate regularity. McKee’s 1,500 acre project was the product of assuming that the good times would roll indefinitely, and most of his properties were purchased during the pre-crisis period between 2003 and 2007. By the time he turned to Jefferson City in pursuit of the Distressed Areas Land Assemblage Tax Credit in 2007, the warning signs were building. By 2009, when McKee publicly declared he would develop $8 billion of new and rehabilitated properties and create 22,000 jobs, the recession had already begun. The grandiose plans seemed more like a cover story to seek additional public subsidy than a realistic framework.

The fire at Crunden-Martin is a reminder that St. Louis never fully recovered from the pre-2008 bubble its developers blew. They were not alone in this, as the early 2000s administration of then-Mayor Francis Slay loaded up even far-fetched schemes with incentives. Economist David Harvey has written that the saddest outcome of the crash of 2008 was that it further accelerated the uneven geography of development and exposed the inability of government to adequately remediate the local consequences. Crunden-Martin was one of the rare speculative properties that had actually finally found a path out of the carnage of the pre-2008 debt collapse. Yet its blaze is a powerful reminder that St. Louis is still putting out fires lit twenty years ago or longer in an economic moment disavowed before its consequences were ever fully inventoried.